Delving into the divides

The disunited colours of Mostar

In ‘Čudna jadna – od mostara grada’, one of the most famous songs about the city, Biba endures a “strange pain from the city of Mostar”, having been “hurt by love”. And so it is that many leave Mostar with a similar pain; the pain of the destruction wrought on the Old Bridge. Mostar’s people are rarely discussed, the victims of the war being harder to grasp compared to the destruction of a bridge. And yet it is the youth of Mostar who grapple to contend with the legacies of a conflict that preceded their existence.

One enduring memory from a 2003 visit to Mostar is the ruins of Musala square blanketed by fashion billboards offering a glamorous and utopian future; a sharp contrast to an earlier United Colours of Benetton poster featuring the blood-stained clothes of Marinko Gagro, killed in battle near the city in July 1994. Benetton likes to shock, but the realities of war are more shocking still.

Over ten years on, Mostar presents visitors with a new utopia, centered upon the ‘Stari Most’ (‘Old Bridge’) and its surroundings. Initially constructed by the Ottomans in the sixteenth century, the bridge was destroyed by Croat forces on 9 November 1993 after extensive shelling. That it survived the early stages of the war was testament to the improvised defence of old car tyres that protected this vital supply route. After a painstaking reconstruction, involving the retrieval of the sunken original stone, the bridge was formally reopened by Lord Ashdown, then Bosnia-Herzegovina’s High Representative, on 23rd July 2004.

Since then, the bridge – best viewed from the minaret of the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque – has borne the twin burdens of tourism and symbolic pronouncements. Vendors proffer paintings – cubist, impressionist and naive – and other artefacts that endeavour to capture the bridge’s unique arch, with varying degrees of success; their sales techniques often as slippery as the steep bridge’s surface. The bridge’s geometry seems to defy all those who have labored artistically to capture its unique beauty.

Every July, divers plunge head or feet first into the emerald green Neretva – its vivid fertility enhanced by the barren hill-side surroundings – during the annual bridge jump, the 450th manifestation of which takes place in 2016. Mostar – whose name derives from the bridge-watchers who would survey all those entering the city (‘most’ meaning ‘bridge’ in Serbo-Croatian) – is now giving birth to a new generation of bridge-jumpers, each determined to match the bridge’s grace and elegance when plunging like swallows into the chilly river beneath.

Once a symbol of the country’s destruction, the bridge has since become a symbol of the city’s supposed reunification; even if many locals insist it lacks the sparkle and sophistication of the original. Yet the Old Bridge has also become the limit of what people know or see about Mostar, with tourists predominantly confined to the ‘East’ (save for a slither of the old town on Mostar’s other bank). Few stay more than a few hours, slated to return to Dubrovnik once selfies on the bridge have sufficed. The so-called ‘West’, for once, holds little attraction.

In the process, foreign visitors to Mostar unintentionally or unconsciously replicate the day-to-day dynamics for many in the city. A recent TV series, Perspektiva (‘Perspective’), focused on the attitudes of the young in Mostar; mainly those too young to remember either the war or the history of co-existence that preceded it. One young Croat, Ante, declared that he had never been to – let alone across – the Old Bridge. The bemused and furious reactions eventually lead Ante to face his fears and cross into the unknown. Whilst physical connections have been rebuilt, psychological barriers remain.

And yet it is in the ‘West’ where part of Mostar’s new narrative is gradually and hesitantly emerging. The ‘Prva’ or ‘Stara’ Gimnazija (‘First’ or ‘Old’ Gymnasium) – formally named after one of the city’s most famous sons, the poet Aleksa Šantić – dominates one corner of the Spanish Square, scene of the so-called 2012 “chocolate mess” staged in response to football fan violence that accompanied Croatia’s European championship loss to Spain. The Gymnasium is one of the city’s architectural landmarks. Constructed in 1898 during Austrian-Hungarian rule, the Gymnasium was inspired by the Moorish Alhambra palace in Spain. Though heavily damaged during the war, it now stands bold and vibrant, its yellow and orange horizontal stripes a reminder of the diversity of influences that shaped the city.

The Gymnasium – once one of the finest schools in the former Yugoslavia – is now simultaneously home to the United World College and one of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s divided schools. The former entices leading students from across the globe, the latter divides students on the basis of their ethnicity, with Bosniak and Bosnian Croat students learning from different curricula. Two-schools-under-one roof have become one of the defining features of education in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Over fifty schools in the Federation, one of the country’s two entities, operate under the principle of ethnic segregation, with students either using separate parts of the school or attending at different times of the day.

Next to the Gymnasium, outside Mostar’s town hall, lie the broken fragments of a memorial to fallen soldiers erected by Bosniak war veterans’ associations, damaged by an explosion back in 2013. It stands next to a rival commemoration for those who fought for the Croatian Defence Council (Hrvatsko vijeće obrane, HVO), which has also been attacked. Remembering the past remains an emotive and divisive subject. When asked to agree upon a ‘symbol of solidarity’ for Mostar, the local community eventually voted for Bruce Lee – whose statue can be found in Zrinjski Park – over both the Pope and Gandhi.

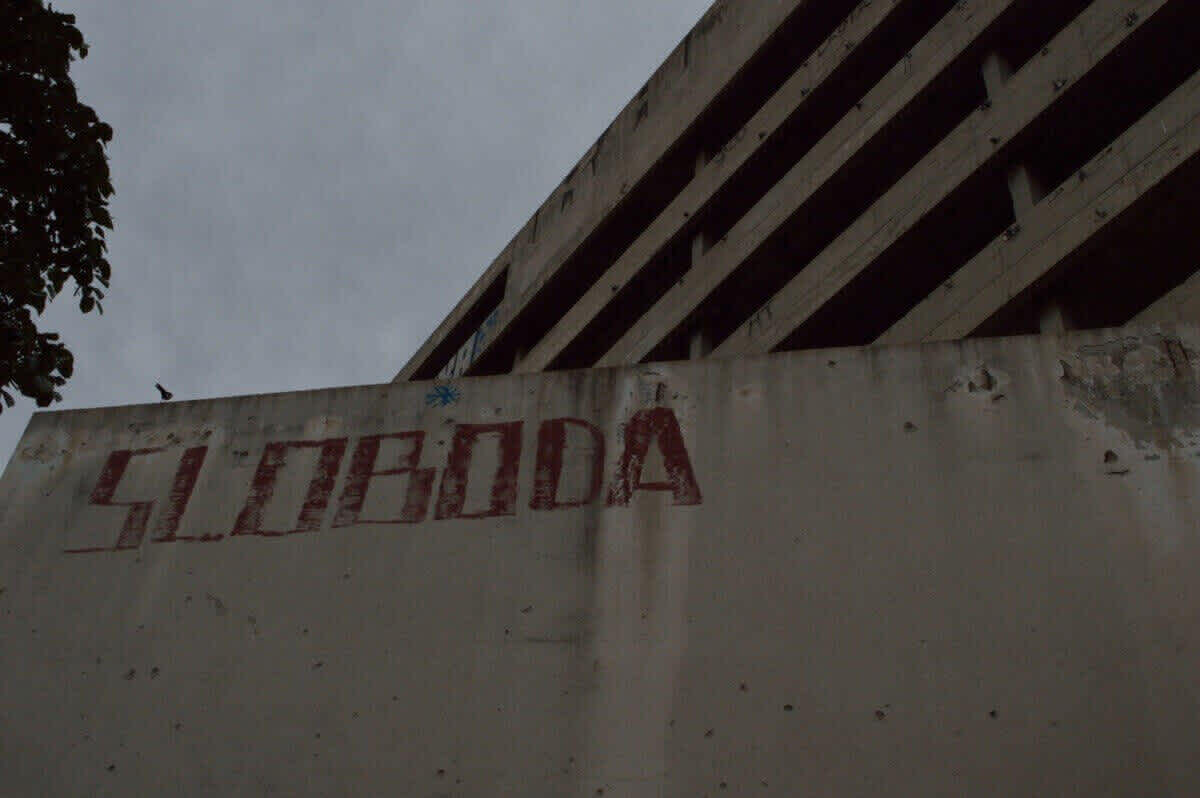

From the Gymnasium one can’t miss some of the most striking elements of Mostar’s war. Sniper Tower (also known locally as the ‘Glass Building’), a former bank which now lies derelict, decorated with graffiti and artwork, with the shell of a revolving door guarding its entrance. “We are all living under the same sky”, reads one message; a sky from which bullets rained down on targets human and man-made. From the top-floor, the frontline is clearly visible, yet rapidly disappearing. In one property, an exposed doorway reveals a tiled staircase with a once eloquent marble bannister; part intact, part displaced. The persistence of such features evokes human life and loss more than any bullet hole.

The city itself is witnessing parallel and divergent paths of redevelopment on either side of the Neretva. Whilst the ‘East’ regenerates its Ottoman architecture and heritage (though many buildings remain abandoned), the former front-line on the predominantly Croat side is simply being knocked down and replaced, the diversity of Mostar’s skyline rapidly replaced by monotony. In the process, there is a profound danger that the new Mostar will turn its back on the old; that the destruction of the city’s cultural heritage through war will be eternalised in peace.

In ‘Čudna jadna – od mostara grada’, one of the most famous songs about the city, Biba endures a “strange pain from the city of Mostar”, having been “hurt by love”. And so it is that many leave Mostar with a similar pain; the pain of the destruction wrought on the Old Bridge. Mostar’s people are rarely discussed, the victims of the war being harder to grasp compared to the destruction of a bridge. And yet it is the youth of Mostar who grapple to contend with the legacies of a conflict that preceded their existence. The Old Gymnasium is one place where desegregation is gradually but surely occurring; a place that will hopefully become not only a symbol but also a source of reconciliation and co-existence. Mostar remains divided, but we all must cut across and delve into these divides.

This piece was originally published by Balkanist Magazine.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian