“A place of endless mourning”

Oradour-sur-Glane massacre

It was described as an “exemplary action”; a surprise attack possibly designed to discourage would-be resistance fighters and their communities. The devastated village, near Limoges, became a permanent monument to the massacre thanks to a decree by French President, Charles de Gaulle, and today stands as a vivid reminder of the horrors of war.

The hilly, forested landscape of Limousin, replete with its isolated farms, provided an ideal setting for resistance fighters; especially as opposition mounted to the Vichy Regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain. Its capital Limoges was ultimately dubbed the “capital of the Resistance". The memorial centre at Oradour relays some of the remarkable stories of resistance by courageous individuals such as Georges Guingouin - prefect of the Maquis of Limousin, a group of rural guerrillas spearheading the resistance - who was dubbed the "the madman of the woods."

On 7th June 1944, the Resistance captured Tulle, a village near Oradour-Sur-Glane. The response of the 2nd SS Panzer Division "Das Reich" deployed in Limousin was swift and devastating. In the reprisals that followed, 99 civilians were hung and 149 deported to Dachau. Oradour-sur-Glane, however, was not renowned for resistance activity, unlike nearby Oradour-sur-Vayres, leading some to assert a case of mistaken identity.

Other hypotheses have been advanced for why Oradour-sur-Glane was targeted. Helmut Kämpfe, a major in the Waffen SS, was captured by the Resistance on June 9th, and subsequently found dead; either executed upon Guingoin’s orders or killed whilst trying to escape. The attack on Oradour-sur-Glane is therefore deemed by some an act of revenge for Kämpfe’s death. Whatever the motive, the despicable crimes committed in Oradour bore all the hallmarks of the Nazi’s vicious campaign on the Eastern Front.

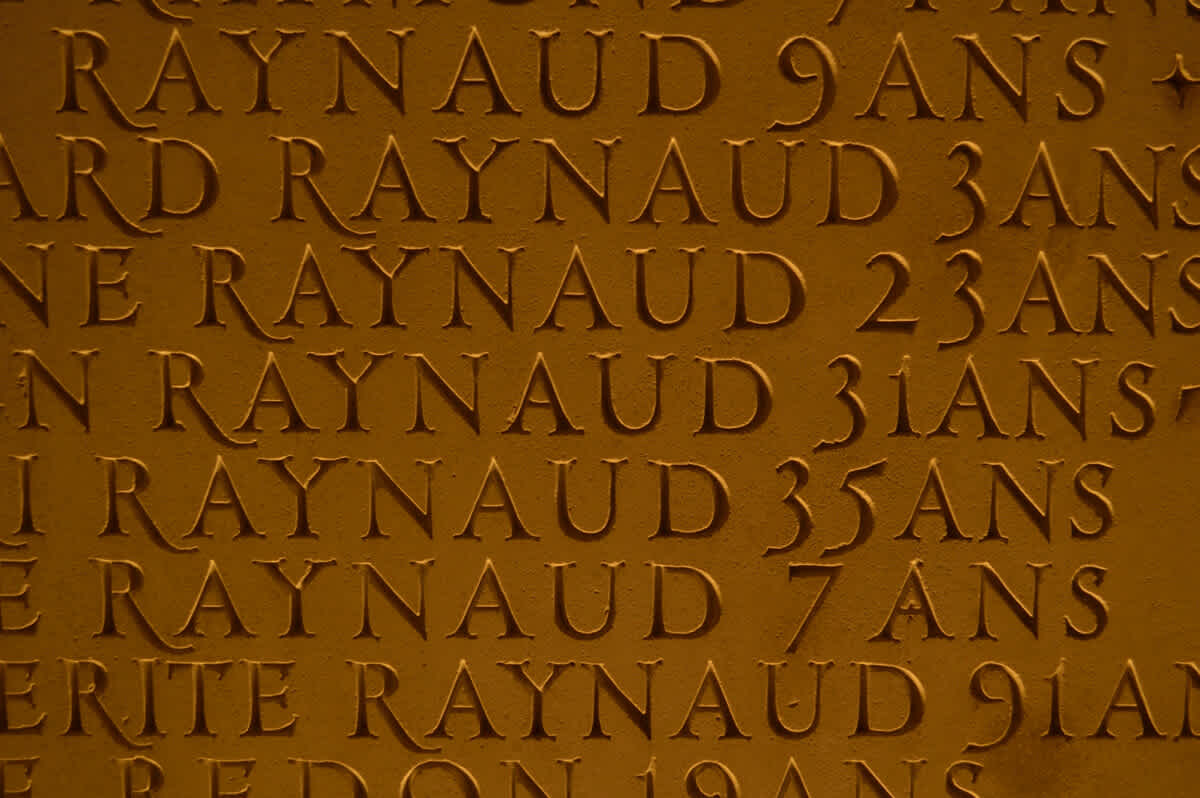

Today the tram tracks with their overhead power lines still guide visitors down the main street - past the Avril Hotel, Denis’s wine store and the Beaulieu workshop - towards Champ de Foire, Oradour’s fairground, where the car of Doctor Desourteaux has sat abandoned for over seventy years. Here the village’s male population were rounded-up to be executed. A little further on - beyond the Girls' school and Desourteaux's garage - lies the roofless Catholic Church where some 450 women and children were slain. The ferocity of the killings was such that fewer than 10% of the victims’ bodies could be identified. Amongst those victims were 25 Spaniards who had sought sanctuary from the Civil War, along with those displaced from Alsace and Lorraine.

Every building in the village had been torched. Plaques on the ruined buildings recall the function that they once served - bakery, the children’s schools, epicerie - along with the names of their owners. Remnants of sewing machines, bicycles, boilers and clothes racks, plus burnt out cars and other machinery, provide manmade reminders of ordinary village life. Oradour-sur-Glane is a nurtured ruin; not abandoned to nature, but preserved to ensure the broken fragments can tell their story to future generations.

Despite the preservation of memory, there is a strong sense that justice has never been served. A 1953 military tribunal in Bordeaux found only 20 defendants guilty, with Eastern Germany preventing the extradition of other perpetrators. 14 of those were French nationals of German ethnicity from Alsace, all but one of whom claimed that they been forcibly recruited by the Nazi. The uproar in Alsace and the pragmatism of post-war reintegration lead the French parliament to grant amnesties to those Alsatians recruited against their will, sparking furious protests in Limousin. By 1958 the remaining defendants had been released. General Heinz Lammerding who ordered the attack was never extradited.

Seventy years on, in January 2014 the state court in Cologne charged 88 year-old Werner Christukat, 19 at the time, with the murder of twenty-five and being an accessory to murder of hundreds more. Though Christukat conceded to being in the village at the time, he claimed that he had not been directly involved. The case was eventually dropped in December 2014 due to a lack of evidence. Whilst further reinforcing the sense that justice continued to elude the victims of Oradour, it served as another important reminder of how Europe to this day pursues the perpetrators of atrocities committed during the Second World War.

A sign at the entrance to the village today implores visitors to remember. As Second World War survivors become a rarer commodity, so the human dimensions of remembrance are increasingly lost. War has in many respects been sanitised and censored by contemporary media. A certain numbness accompanies images from Aleppo, despite the very victims of this and other tragedies now arriving daily on Europe’s doorsteps.

Oradour-sur-Glane lies just over a hundred kilometres from the Cognac birthplace of one of the architects of European unity, Jean Monnet. Such tragedies are a reminder of the devastation that was once wrought upon Europe, and the importance of the continuing pursuit of justice for victims. Oradour-sur-Glane remains a “place of endless mourning” and a permanent reminder of the “martyred village”; not just for the martyrs of the village itself, but for all those who perished at the hands of terror, East and West.

A longer version of this piece was originally published on OpenDemocracy.

Oradour-sur-Glane Directions

The city of Oradour-sur-Glane is located in the department of Haute-Vienne of the french region Limousin.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian