An unusual day out

Chernobyl’s white wonder wasteland

As the world flirts with the prospect of another nuclear fallout - whether from rogue leaders or accidents like Fukushima - moving beyond purely academic understandings of the impacts of nuclear catastrophe is more imperative than ever. ‘Chernobyl Prayer’ by Nobel Prize winner, Svetlana Alexievich, goes some way to addressing the balance with its powerful monologues, but is no substitute for the immediacy offered by the site of the twentieth century’s worst civilian nuclear catastrophe.

Though events at Chernobyl are finally well-understood, the human toll remains victim to a combination of amnesia, apathy and bureaucracy (both intentional and incompetent). ‘Chernobyl Prayer’ by Nobel Prize winner, Svetlana Alexievich, goes some way to addressing the balance with its powerful monologues, but is no substitute for the immediacy offered by the site of the twentieth century’s worst civilian nuclear catastrophe.

Guided tours to the exclusion zone around Reactor Four of the Chernobyl power plant - covering some 2,600 square kilometres, equivalent to the size of Luxembourg - provides a firsthand glimpse of the wasteland created by the events of 26th April 1986.

We are offered the chance to hire our own dosimeter (to measure our radiation exposure), but politely decline. Ignorance is atomic bliss. Our guide attempts to install some winter cheer by insisting that it is the best time of the year to visit; adding dryly, “there are no leaves or radioactive dust.”

I watch my breath condense and my lack of control over its direction of flow. Neighbouring Belarus, often neglected in the Chernobyl collective memory, suffered most from the winds that pushed the radioactive clouds northwards.

In the explosion’s immediate aftermath, villages surrounding the reactor were flattened and all building materials buried; including the unfortunately named village of Kopachi (meaning ‘Gravediggers’ in Ukrainian). Cats and dogs were shot, and pigs and cows relocated. Many thousands were made nuclear IDPs (internally displaced persons), though with inexplicable delays that ultimately cost many lives.

Others villages such as Zalissya - which once boasted a collective farm and cotton factory - were simply abandoned. Bent birch trees now form an arch over the main street, where the Cultural Centre (constructed in 1959) proudly stands, bearing the first reminders of the Soviet Union (a hammer and sickle; a five pointed star). A Lada slowly decays; “testament to the quality of Soviet steel”, my guide claims without a whiff of irony.

The remnants of daily life - the local co-co-operative shop, pieces of clothing, creaky floorboards, a bucket - remind me of the village of Oradour-sur-Glane in France; a living memorial to the 642 inhabitants massacred by the Nazis. Two almost identical scenes and both man-made; one of war, the other of the so-called "peaceful atom" (as nuclear power was dubbed in the Soviet Union).

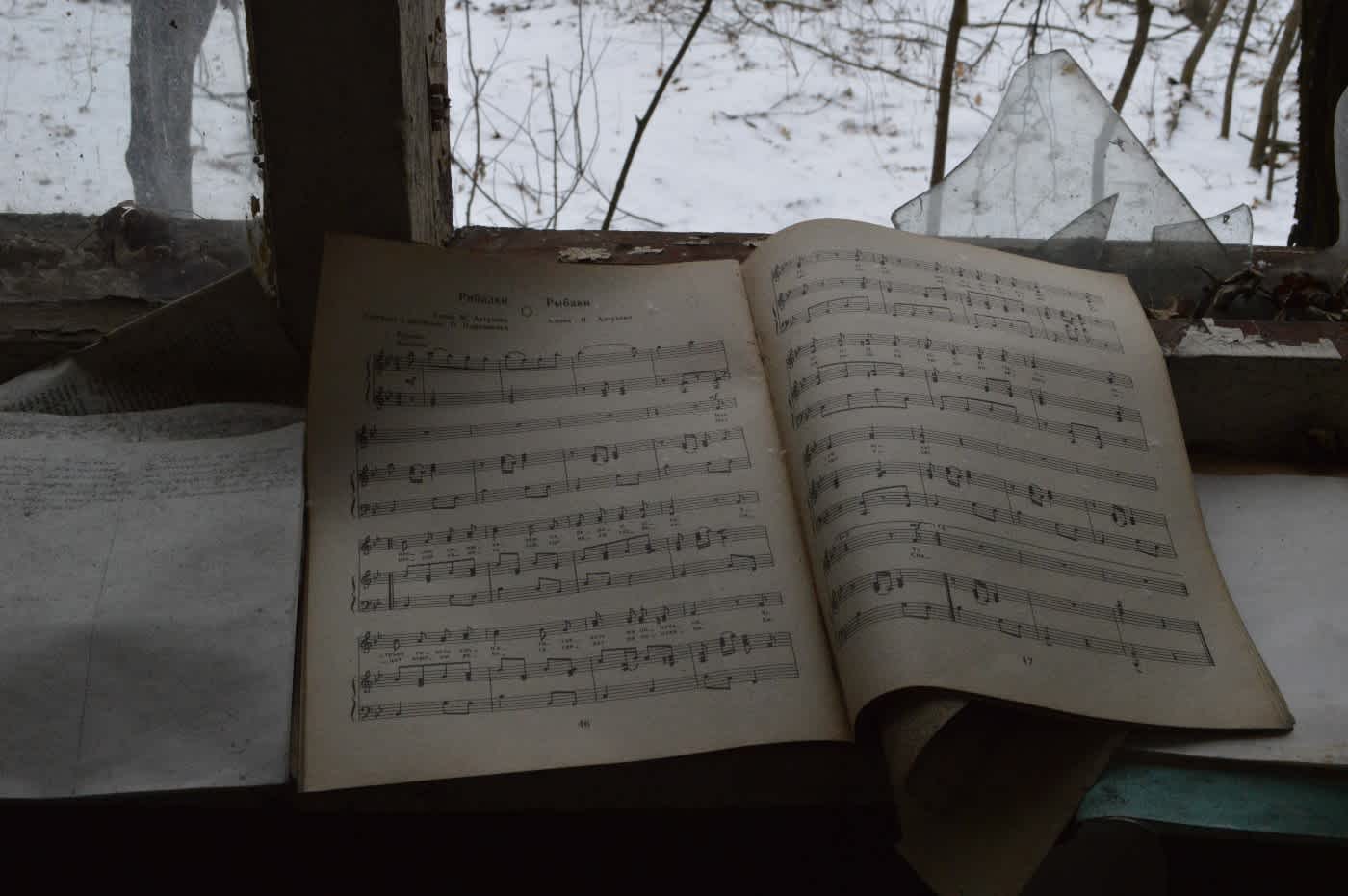

We tour an abandoned kindergarten, where demonic looking dolls await reunion with their rightful owners. Bunk beds are empty and rusting. Sheet music sits on the window sill waiting to be read; the chalkboard eager to educate. Though the Chernobyl disaster was only just over thirty years ago, I wonder how many of these children survived the initial radiation exposure.

The reactor itself - now encased in the world’s largest movable structure - is rather unremarkable; except for the stories of those who fought gallantly to prevent an even worse catastrophe from unfolding, one which could have rendered almost half of Europe uninhabitable. Radiation levels here are 0.55, compared to 0.14 when we left Kyiv. A nearby memorial to the firefighters is dedicated “to those who saved the world.” It is not an overstatement.

The readings on our guide’s dosimeter spike and a nauseating sound is activated in the so-called ‘Red Forest’; its name deriving from the colour the leaves turned due to contamination, before the trees were chopped and buried. Like a gold digger in his pursuit of contamination hotspots, our guide is little deterred by the yellow radiation warning signs (with a symbol resembling an extractor fan). He reels of his years of service and number of children (two) to reassure us.

Further on is the town of Pripyat, where time has all but stopped. Down Lenin boulevard, past empty six-to-eight storey apartment blocks, almost identical to one another, we reach an ‘experimental‘ Soviet supermarket, where shopping trolleys await customers in the fruit and vegetable aisle.

No longer does the amusement park’s yellow ferris wheel turn. Our guide tells us it never really did, save to distract local residents from the uncertainties of the days following the reactor's explosion. The bumper cars have ceased jockeying for position, and the plastic boats have stopped ascending and falling. The nearby stadium may now be overgrown, but queues had already long since ceased to form at the turnstiles.

In the cultural center there is a picture of two Communist functionaries (none of the guides knew their names) and poster with a message from Lenin. “Learn, Learn, Learn” it reads. By now the lesson should be clear, but not necessarily heeded.

As the world flirts with the prospect of another nuclear fallout - whether from rogue leaders or accidents like Fukushima - moving beyond purely academic understandings of the impacts of nuclear catastrophe is more imperative than ever. Digest the writings of Alexievich and the monologues of her subjects, then see first hand some of the lasting impact of such tragedies. Chernobyl is no better starting point.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian