Rebuilt ‘better than before

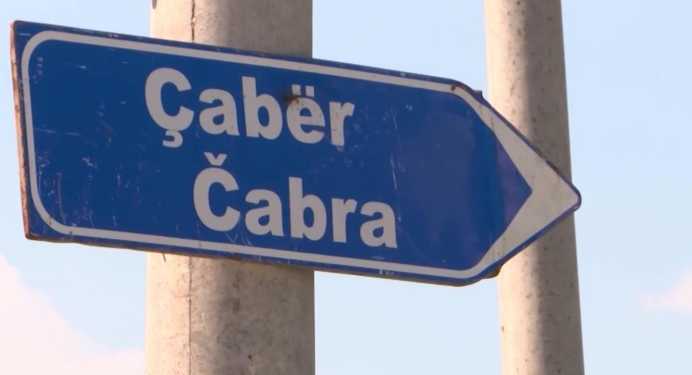

Çabër/Čabra in north Kosovo

The village of Çabër/Čabra is nestled on the north bank of the Ibar, down a rather steep embankment from the main road between Mitrovica and Zubin Potok. Ninety five per cent of its pre-war population returned to a village that I’m told was rebuilt ‘better than before’. This extract from Ian Bancroft’s new book, ’Dragon’s Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo’, explores why many of its residents turned their noses up at the possibility of making a home elsewhere.

The village of Çabër/Čabra is nestled on the north bank of the Ibar, down a rather steep embankment from the main road between Mitrovica and Zubin Potok; sitting at the foothills of some of the final slopes of the Rogozna mountain range; traversed by the backroad between Zvečan and Zubin Potok. Ninety five per cent of its pre-war population returned to a village that I’m told was rebuilt ‘better than before’. I am interested to learn why these residents turned their noses up at the possibility of making a home elsewhere. It is the Friday prayer—or Jumu’ah, the most important of the week—held just after noon. I choose this day because it guarantees a covey of people milling about afterwards for spontaneous reflections on the past, present, and future. It is a simple white mosque with a moderate dome and minaret, both capped with silver steel gleaming in the midday sun. A girl and her mother— the latter in a tight, white hijab—wait in their car whilst the men prey. The younger gentlemen scoot off on bicycles and the middle aged gentlemen purposefully on foot, leaving the elderly gentlemen to amble along the road in pairs. Others are reunited with their families, driving off in various directions.

An elderly gentleman in a baggy black cap, Hajrula, approaches me just as intently as I do him. He speaks fondly about his days as a baker in Zubin Potok, and the distribution channels that took him to various settlements throughout north Kosovo, ultimately tying him to this corner of the world. In a week that saw protests outside an Albanian owned bakery in Belgrade, it was a timely and necessary reminder of the relationships that the most rudimentary foodstuffs, particularly bread and ice cream, can help establish between people.

Another elderly gentleman, Sefer, his ears piqued by my questioning, volunteers to explain how, ‘not a single house was left untouched by the war’. All have been rebuilt; some with the ubiquitous red bricks still on display, others with shiny new facades. Most are surrounded by high walls and steel gates. I peek through a few open doors to find well-maintained and manicured gardens. This is a simple settlement of dispersed houses, with little visible structure. Most strikingly, Sefer speaks not about security, but about the lack of jobs. ‘We can’t keep the young people here’, he groans, before glancing towards properties that he presumably knows have been vacated. It is a familiar tale up and down these lands; young people leaving in droves in search of gainful employment.

A war memorial to twenty victims has been erected at what seems to be the village’s main junction. Two entries in particular stand out—‘Latif E. Uka—1999–1999’ and ‘Emine Z. Selimi—1913– 1999’—one whose life story hadn’t even turned its first page; another whose final page would be to succumb in another war. Three kids play football opposite, whilst another boy pretends to be a sniper; raising a white stick to his shoulder, closing one eye, and placing the other down its length. His friend (or so I presume) pops his head out from around the corner; typical kid’s stuff. Two other children race me out of the village on bicycles that they’ve yet to grow into, standing tall and peddling with youthful abandon. I glance through the rearview mirror to see them struggling to catch their breath.

Revered by Kosovo‘s Serbs and Albanians alike

Sokolica Monastery‘s ‘miracle-making’ prowess

There is a local saying, ‘a blind person or a cripple can be born in Čabra, but never a stupid person’. People here are renowned for their nous and intelligence, and, it seems, their pragmatism and perseverance. I once again struggle to reconcile the tranquility of this place with the trauma of war. When the spectre of land swap raised its ugly head—namely that Serbia would retain or obtain north Kosovo, in return for part of its predominantly ethnic Albanian south-east, referred to by some as the ‘Preševo Valley’—it was Kosovo Albanians here who expressed the most profound concerns that they would once again be left to fend for themselves in a context of disintegration, completely marginalized from those that they look to for support.

Çabër/Čabra

The village of Çabër/Čabra is nestled on the north bank of the Ibar.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian