Revered by Kosovo‘s Serbs and Albanians alike

Sokolica Monastery‘s ‘miracle-making’ prowess

Banjska [Monastery] is often mentioned by historians as the original home of one of the Serbian Orthodox Church’s treasures, the sculpture of the Virgin Mary (‘Theotokos’) with Christ the Child, which dates back to the fourteenth century. Abbot Danilo tells how King Milutin engaged the best craftsman from Byzantium and Dubrovnik to produce such a sculpture, but is unclear when it was removed from Banjska. It is a hypothesis Mother Makarija, Abbess of Sokolica Monastery, unyieldingly refutes for ‘theological reasons’. Banjska was consecrated for Sveti Stefan (Saint Stefan), not the Holy Virgin, she clarifies; adding that confusion arises because Banjska was modelled upon the twelfth century Studenica Monastery, south-west of Kraljevo, Serbia, which was dedicated to the assumption of the Holy Virgin. The Abbess, her lame right arm propped pensively under her chin, proffers an alternative; namely that the sculpture was housed in one of the churches constructed by the Saxon miners, themselves Roman Catholics, before Ottoman incursions necessitated its removal and safekeeping. Sokolica was an ideal refuge. ‘There is no road leading up the hill, so the Turks were never here’, the Mother reasons whilst smiling sardonically. Its ultimate provenance is unclear; though the Abbess draws parallels with sculptures she encountered during her theological studies in Salonika, Greece; Serbia having apparently lacked the workshops to produce such a masterpiece at that time.

The sculpture’s ‘miracle-making’ prowess is revered by Serbs, Albanians, and others alike, particularly for its perceived powers of fertility and healing. The Abbess recounts how a husband and wife, the latter fearing divorce should she fail to conceive, pray at the monastery. Some twenty years later the wife returns to seek a bride for her son. A Greek soldier is persuaded by his grandmother to break his daughter’s silence by bringing her to the monastery. Once plied with prayer and Coca-Cola, she turns upon leaving and shouts ‘Ciao Mati!’, a term of endearment for an elderly woman that reduces her father to tears. The Abbess tells how a number of Nato officials past and present have visited with their wives to pray and purchase icons, and ‘all received children’. The Holy Virgin ‘helps all those with hope and belief’, regardless of their faith. Hundreds of tokens of gratitude are displayed beneath the metre high marble sculpture; now a murky white, its original blues and reds—depicting human and divine nature, respectively—having faded. Poet Rastko Petrović, in his 1925 essay, ‘The Holy Peasant Woman in Kosovo’ (‘Sveta seljanka na Kosovu’), recounts how, ‘I needed almost an hour to free Her [the Mother] from clothes and jewelry which villagers had lavished upon Her … Only Her free face could be seen’.

The monastery is reached via a steep, winding road, though the village of Malo Rudare, past crosses assembled out of logs to guide the route. Delicately balanced boulders resemble a mother cradling her child; life imitating religious artefact. Sokolica derives its name from the Peregrine Falcons (‘Soko’ in Serbian) nested here. It looks out over a vast expanse of hillside as if viewed through a fisheye lens; the trees a rusty orange as the long winter draws to a close. It shares the aura of peace and serenity common to nearly all of the monasteries in the region; save where humans have approached with ill-conceived and poorly executed constructions, like those which infringe upon the Patriarchate of Peć. It survived as an oasis of tranquility, albeit without permanent residents, even as war engulfed the rest of Europe.

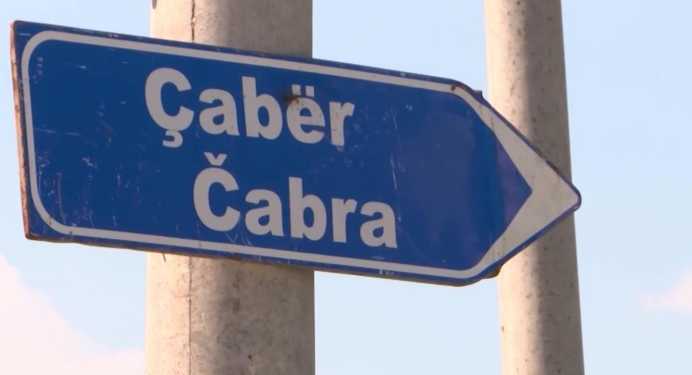

Five flags flutter beneath; two of the Republic of Kosovo, three of neighbouring Albania. This is the resting place of Isa Boletini—meaning ‘of Boletin’, the village next to the monastery—one of the leaders of the 1910 Albanian Revolt. The school also bears his name. Every 28th November, Albanian Flag Day—the date on which it declared independence back in 1912—convoys of people make their way up the hillside to pay homage to this national hero, whose remains were laid to rest here in 2015. Boletini has something of a caddish reputation. Upon meeting a supposedly ammunition-less Boletini at the British Foreign Office in London, Sir Edward Grey, then Foreign Secretary, commented that, ‘General, the newspapers might record tomorrow that Isa Boletini, whom even Mahmut Shefqet Pasha could not disarm, was just disarmed in London’. Isa, pulling a second pistol out, replied, ‘no, no, not in London either’. He also had little time for Serbs, boasting in 1913 that ‘when the spring comes, we will manure the plains of Kosovo with the bones of Serbs, for we Albanians have suffered too much to forget’. It will not surprise you to learn that Boletini has a statue of his own; an iron construct in south Mitrovica, just beyond the Main Bridge, which looks northwards over the river.

With scarves for the women and black tea for the men, the Abbess fostered ties with her immediate Albanian neighbours upon taking residence in 1991. Any surplus from the cultivated monastery lands (whether nuts, raspberries, peaches, or cherries) were donated; only the local school rejected offers of firewood, saying they wanted nothing to do with the ‘kishë’—the Albanian word for ‘church’, which the Abbess uses for emphasis, before wondering ‘what kind of teachers these children have?’. ‘We simply had to live together’, the Abbess insists. The walls that today surround the monastery were constructed, on the Abbess’ instructions, by the very same neighbours, ensuring they maintained a ‘special relationship with the wall’. As Nato’s bombing campaign commenced, the monastery’s first neighbour, whom she describes as ‘a noble man’, reassured her not to be ‘afraid of me and my children. I’ve taught them to respect the monastery’. They patrolled the borders of its property, fearing that—in the words of the Abbess—‘should Albanians from far away damage the monastery, then the Serbs will think we were responsible’.

Monasteries may no longer serve as the fulcrum of community life, but their revival has provided spiritual enlightenment for many during these darker moments of history. They have also assumed a profound political relevance; integral parts of on-going debates about Kosovo and its significance to the Serbian Orthodox Church and, ultimately, Serbia. Too many uniformed and uninformed individuals have entered these four walls in recent years, each endeavouring to reassure the faithful that their security concerns are well-heeded. Many of those were religiously illiterate; prone to seeing the monasteries as purely remnants of bygone age. Their protection, nurturing, and revitalisation, however, is more essential than ever to the future peace and stability of these hallowed lands; so too the reconstruction of all mosques and other aspects of Islamic heritage destroyed in the all too recent past. Failure to do so will only serve to sow more dragon’s teeth in this corner of Kosovo.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian