Freed from commodification

Beyond Cuba’s cliches

The commodification of various elements of Cuba’s revolution and culture has created a cliched idea of what the country is and was; an idea readily propagated by those keen to ‘sell’ Cuba to the tourists, and embraced by tourists eager for a plastic sense of revolution, reinforcing one another in a reproductive web of kitsch.

Elpidio Valdes is still fighting to liberate Cuba from Spanish colonialism, at least for those schoolchildren tuning in daily to his cartoon endeavours. In Year 59 of the revolution, the message of liberation and self-determination remains as defiant as it did when Jose Marti, Cuba’s revered and unifying face of independence, sacrificed his life by charging the Spanish at the Battle of Dos Ríos.

Almost sixty years after the triumph of Fidel Castro and his ‘barbudas’ (‘bearded ones’), the much-trumpeted Cuban Revolution is sits in an uneasy symbiosis with new hordes. Droves of tourists, wooed by nostalgia for and legacies of a revolution that many residents believe is still on-going, descend upon Cuba in ever greater number, each seeking their own particular piece and flavour of history.

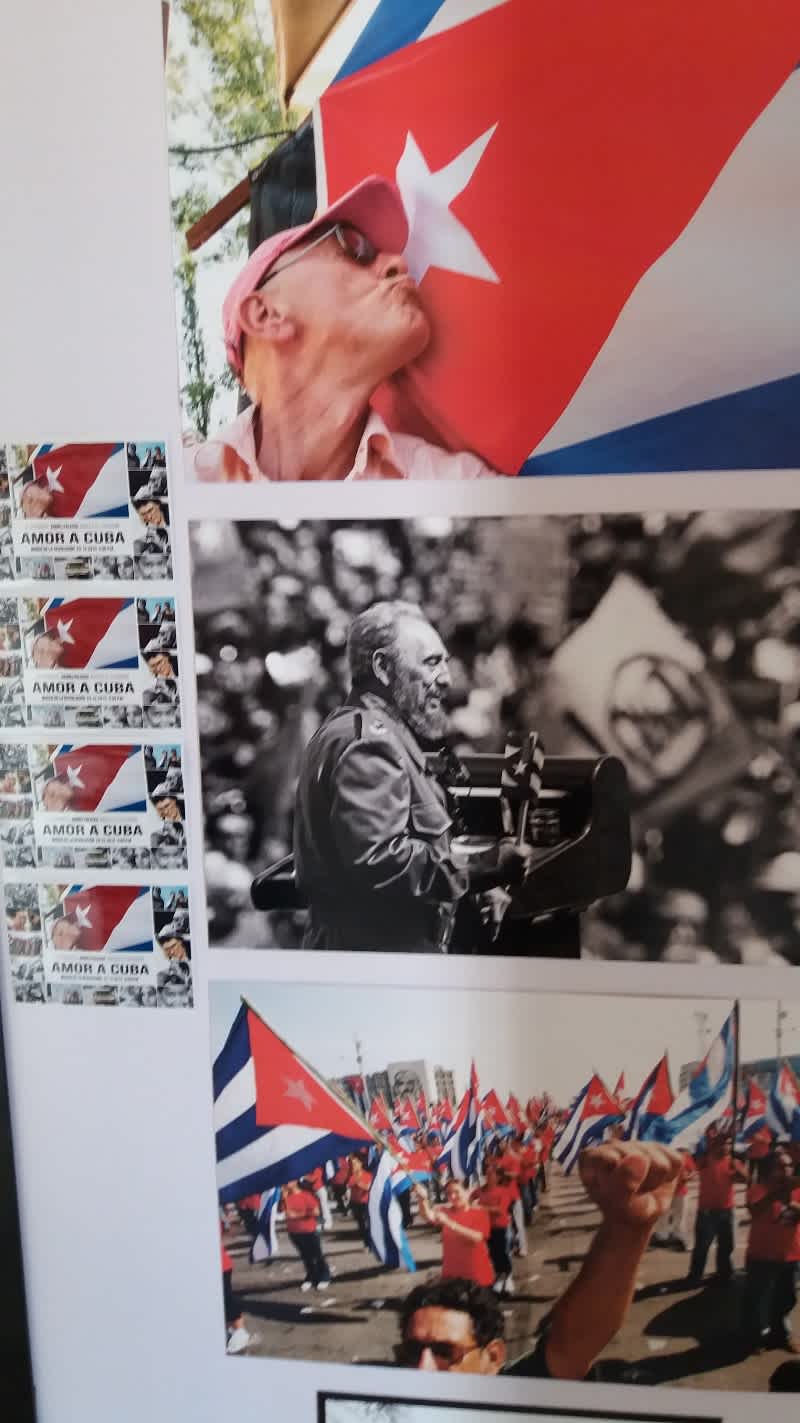

The commodification of the revolution has become a mainstay of Cuba since the collapse of its sponsors. Though Fidel shunned various forms of personal representation, especially the construction of statutes, his image - and that of his comrades, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos - adorn all manner of merchandise; from ashtrays to bottle openers, T-shirts to cigar lighters. It reminds me of sites of religious pilgrimage, where the supposed sanctity of the individuals is diluted by the hawkers proffering kitsch souvenirs.

Such commodification has spilled over into the cultural domain, where renditions of Buena Vista Social Club and Guantanamera ring out from street side bars and restaurants like a broken jukebox. Even the most tenuous connections with the Social Club demand showgoers pay a pretty premium. The last surviving member seems to live on eternally.

Rehashed Chevrolets from the fifties, retrofitted with modern Hyundai engines, tootle along the Malecon, Havana’s wave-swept promenade, where local residents convene in the evening to listen to music and regale tales. The city’s casinos - a symbol of American imperialism, and the crime and corruption of the Mob in the post-war years - are making a return, including the famous Hotel Nacional de Cuba.

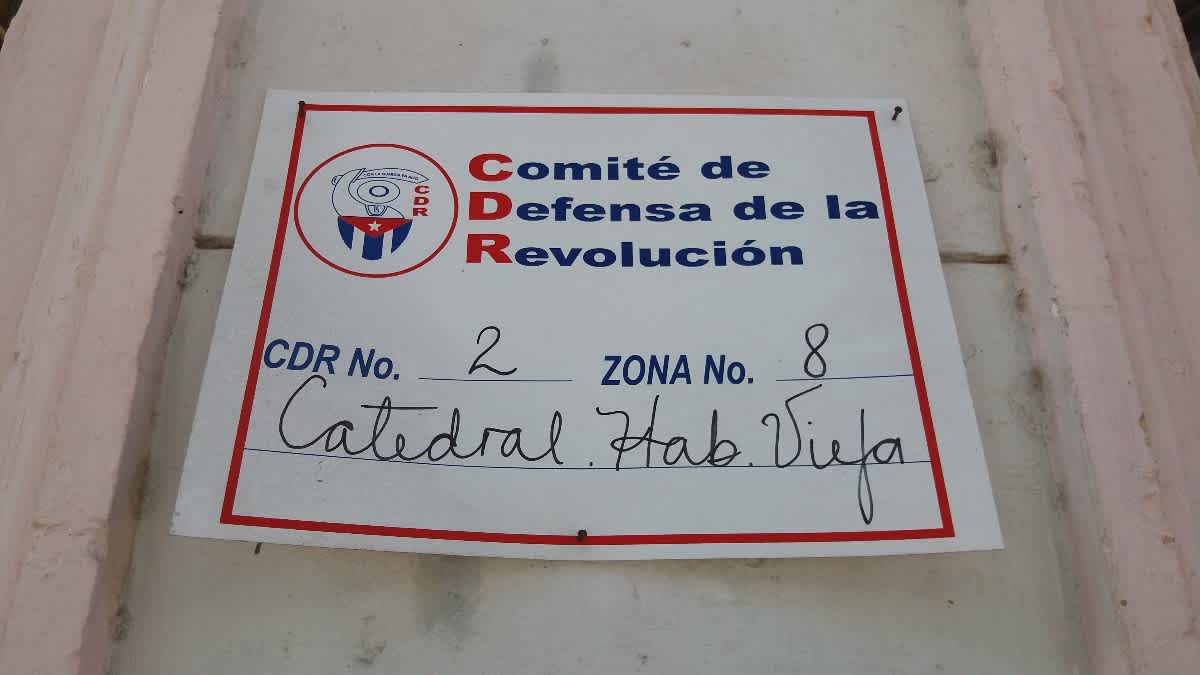

Posters extolling the virtues of labour, solidarity and other revolutionary traits have become popular souvenirs, whilst tourists pose for photographs outside the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (though it is far from clear what they actually defend these days).

Cuba is nurturing the past whilst trying to stake out its future. Havana Vieja (Old Havana) is being painstakingly restored in the manner of Warsaw; obliterated not by war but by decades of neglect. The reallocation of property left the socially vulnerable inhabiting the heart of the city’s colonial treasure without the means to nurture its heritage. The painstaking preservation of its historical architecture has saved one of the city’s eras from another.

Only a few blocks away, the streetlights end and the hustle-and-bustle of normal daily life takes over; plates of rice and beans served up to customers being charged in the Cuban as opposed to Convertible Peso (the latter ). Here the growing complexities and conundrums of Cuba's revolution are visible despite the darkness. Gradual liberalisation has unleashed a long-restrained entrepreneurial spirit, yet new inequalities are simultaneously straining the very tenants upon which the revolution rests. Cuba remains home to a contradictory notion of internationalism - one that celebrates a range of foreign influences, yet deprives its citizens of access to the internet, who queue up for expensive internet cards to contact relatives who've long-since fled.

The commodification of various elements of Cuba’s revolution and culture has created a cliched idea of what the country is and was; an idea readily propagated by those keen to ‘sell’ Cuba to the tourists, and embraced by tourists eager for a plastic sense of revolution, reinforcing one another in a reproductive web of kitsch.

There is, however, considerable scope for optimism. Alternative venues such as La Fábrica de Arte Cubano are attempting to articulate different takes on contemporary Cuban identity through art, music and cuisine. They are no less emboldened in the ideals of the revolution, but grapple creatively to express and harness the country’s evolution. Visitors to Cuba would do well to look beyond the cliches in search of the emerging Cuba - vibrant, proud and emboldened.

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian