A site of repressed memories

Gazivode Lake

Though landlocked, Zubin Potok, which claims around 15,000 inhabitants, boasts a vital frontier between Kosovo and Serbia in the form of the artificial Gazivode Lake (also referred to as ‘Gazivoda’); one of the most strategically important sites in the entire north of Kosovo. Its waters cool the ugly, polluting Obilić power plant just outside Pristina (visible from the north when not enveloped in its own smoke and fumes), whilst serving industry and agriculture (though the water is really too cold for irrigation). Gazivode also parches the thirst of hundreds of thousands of Kosovo households. Its hydroelectric dam—apparently one of the highest in Europe, at some 107 meters—provides a sizeable chunk of the north’s energy needs. This man-made lake keeps Kosovo hostage to Zubin Potok, and vice-versa. Kosovo cannot function without Gazivode, meaning that Zubin Potok cannot merely be allowed to slip away quietly. The two are conjoined like Siamese Twins, who either endeavour to live in mutual peace and harmony, ignoring the intrigued yet intrusive glances of outsiders, or pursue surgical separation, in the process of which one or the other or both may perish. This stark reality is best illustrated by consecutive visits to Gazivode in September 2018 by the presidents of Serbia and Kosovo, Aleksandar Vučić and Hashim Thaçi, to reassert their respective claims; the latter taking a much-photographed tour on the Lake in a hastily arranged boat, accompanied by the heads of Kosovo’s Intelligence Agency and Police.

Ljubiša [Mijačić, an architect and environmentalist] has spent a considerable amount of time pondering the conundrums of Gazivode; an obsession arising from the displacement of two-thirds of his own family when the valley floors were flooded back in the mid-seventies. He hopes that an agreement will be made on the use of Gazivode to the mutual benefit of all, but warns that should conflict continue then ‘Serbia could use its parental rights one way or the other in a century that will be shaped by water scarcity’. As ambitious or seemingly unrealistic as this may sound, Serbia retains the right and capability to divert the flow of the river that feeds Gazivode in order to nourish the populous Sandžak region (as it is referred to by some) in the country’s south-west. He describes such a hypothesis as a ‘bed of nails’, such was the unpopularity of the idea when first posited.

Until the end of the eighties, public discussion about Gazivode was all but forbidden. For some, it was constructed due to these aforementioned water imperatives. Ljubiša, however, is more sceptical, especially because of the rush in which it was completed and the ‘monstrously large’ project which resulted. He points out that two alternatives to Gazivode were considered— Ribariće village and a narrow point next to Kopiloviće village— both of which involved fewer construction challenges and risks. Instead, 3,500 Serbs were forced from their homes in Rezala in order to create Gazivode Lake; a form of ‘social engineering’ that has had profound consequences, particularly given the size of the families here. ‘Every baby will earn its income’, he jokes, referring to the rationale behind large households and their ability to ‘defend against famine’. Rezala possessed some of the most valuable land, with generous harvests of fruit and vegetables. Everyone was involved in agriculture; until, that is, the land was submerged.

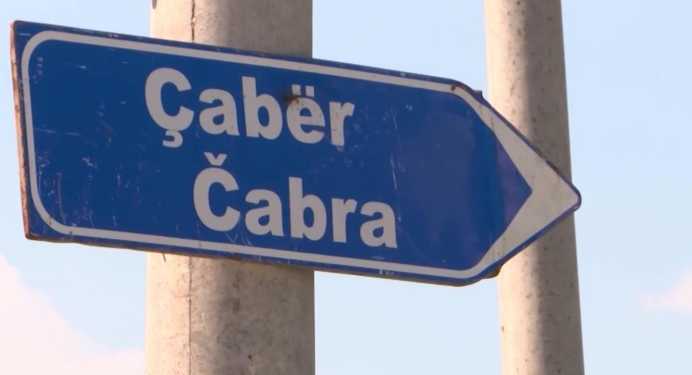

Gazivode Lake in north Kosovo

Gazivode Lake in north Kosovo, described as a 'site of repressed memories'.

Rerouting the river would expose not only the remnants of Rezala, particularly its Cultural Centre, but other legacies of Zubin Potok’s cultural and industrial heritage. Old video from Serbia’s national broadcaster shows how the land once looked, before they illustrate the rising water levels in a rudimentary manner by blacking out part of the screen. As many as eleven other villages were sacrificed, along with three fortresses, four Roman cemeteries, and five medieval churches. Orchards of apple and pear trees were gobbled-up by the lake. A school of etiquette founded by Jelena Anžujska (‘Helen of Anjou’), the mother of King Milutin, also disappeared; a seemingly inexplicable and indictable handling of history. There is also the first hydro-power plant in Čečevo village, renowned for its ‘constantly flowing river’; the Yugoslav authorities having refused to allow for the pioneering equipment to be salvaged. It seems that there is much that lurks beneath Gazivode, leading Ljubiša to call it ‘a site of repressed memories’.

Revered by Kosovo‘s Serbs and Albanians alike

Sokolica Monastery‘s ‘miracle-making’ prowess

Ian is a writer based in the Balkans. He is the author of 'Dragon's Teeth - Tales from North Kosovo' and 'Luka'. Follow Ian on Twitter @bancroftian.

Currently in: Belgrade, Serbia — @bancroftian